While we’ve posted frequently on different aspects of the rigging of the foreign exchange markets (see here, here, and here, for example), we haven’t gone into much detail on one of the largest cases: In re Foreign Exchange Benchmark Rates Antitrust Litigation, Index. No. 13-cv-7789 (SDNY). I’m here to fix that! Today’s post will cover the motions (and cross-motions) for summary judgment, and, at the same time, try to fill any gaps left by our earlier discussions.

The third consolidated amended class action complaint was filed in early 2020, following a 2018 settlement with fifteen defendants. Like those before it, the new complaint alleged that Defendants (namely, Credit Suisse) conspired to fix the prices of currencies in the foreign exchange (“forex”) or foreign current market and brought claims under Sections 1 and 3 of the Sherman Antitrust Act and under the Commodity Exchange Act, 7 U.S.C. §§1 et. seq. The Defendants were dominant dealers in the foreign exchange market. Plaintiffs include both “Over the Counter” (or “OTC”) Plaintiffs (and the OTC Class) and “Exchange” Plaintiffs (and the Exchange Class). The OTC Plaintiffs were direct customers of the Defendants, transacting in various forex instruments (including spot transactions, outright forwards, swaps, options, futures contracts, options on futures contracts, and other similar instruments in the forex market). The Exchange Plaintiffs are those who transacted in these forex instruments through an exchange, rather than with Defendants directly. More than half of forex transactions in the US are “spot transactions,” which involve and outright exchange of currencies between two counterparties; these spot transactions determine the pricing of other forex instruments. The complaint alleges that, from 2003 through 2013, Defendants conspired to fix prices in the forex market as follows:

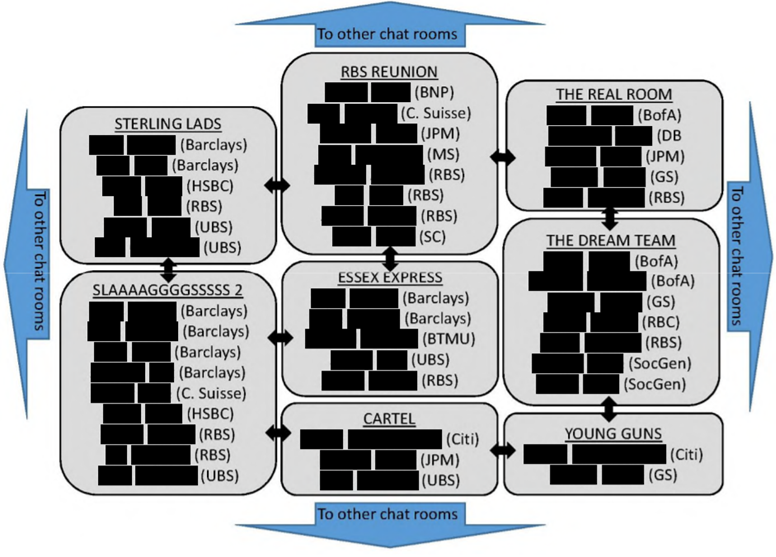

Through the daily use of multiple chat rooms with incriminating names such as “The Cartel,” “The Bandits’ Club,” and “The Mafia,” Defendants communicated directly with each other to coordinate their: (i) fixing of spot prices; (ii) manipulating FX benchmark rates; and (iii) exchanging key confidential customer information in an effort to trigger client stop loss orders and limit orders. Defendants’ conspiracy affected dozens of currency pairs, including the seven pairs with the highest market volume. And due to the importance of spot prices, Defendants’ conspiracy impacted all manner of FX Instruments, including those trading both OTC and on exchanges.

In making these allegations, Plaintiffs point to “thousands of communications involving multiple defendants” which allegedly demonstrate Defendants’ coordination, not just in the spreads they quoted, but in the key forex benchmark rates. They also point out that the existence of the “cartel” is beyond dispute, as the conduct was under active investigation by both the DOJ and CFTC (with several defendants having already pled guilty to conspiracy).

Credit Suisse Defendants Move for Summary Judgment

In April 2021, the Credit Suisse Defendants filed a motion for summary judgment. The brief focused on refuting Plaintiffs’ allegations of a single, global conspiracy among the sixteen Defendants. Specifically, Credit Suisse argues that the various chatrooms and communications on which Plaintiffs rely describe nothing more that “mini-conspiracies in which a small group of traders shared information among themselves, allegedly to the detriment of other Defendant Banks and other market participants.” Further, Credit Suisse argues, not even the cases brought by the regulators support Plaintiffs’ theories, as those investigations were narrower in scope than Plaintiffs’ allegations, and did not posit—nor prove—the existence of a wide-reaching global conspiracy.

The existence of smaller conspiracies is insufficient, according to Credit Suisse, to find an over-arching conspiracy, unless Plaintiffs are able to show that each member of the alleged conspiracy “(1) knew of the single conspiracy and understood the nature of the conspiracy and its scope; (2) intended to join the single conspiracy to further its unlawful objective; and (3) became interdependent upon the other members of the single conspiracy.” Credit Suisse points out that there is no evidence of any in-person or online gathering where all sixteen Defendant Banks met to discuss the conspiracy; that there is no evidence of a “meeting of the minds” reached without such meeting; and that there is no evidence that any of the “hundreds” of forex traders believed that they were part of an all-encompassing conspiracy. Even accepting that each trader “need not have full knowledge of all the details of the conspiracy or its scope in order to be a member,” Credit Suisse argues that the traders at least “need to be aware that the purported conspiracy exists,” and that “even that most basic showing cannot be made here.”

In addition to purported evidentiary issues, Credit Suisse also points to Kotteokos v. U.S. 328 U.S. 750 (1946) to argue that it is improper to attribute the common interest of the banks and their traders – in this case, the fact that the Defendant Banks all preferred and benefited from wider spreads – with the common purpose needed for single conspiracy.

Plaintiffs’ Opposition and Cross-Motion

As might be expected, Plaintiffs take a different view of the evidence. Their brief highlights the high degree of interconnectivity between the Defendant Banks, maintained by a series of chatrooms: all sixteen Defendant Banks were “interconnected through just eight interlocking chat rooms,” a diagram of which is included below.

Plaintiffs described the overlap between these groups, and others, which individual traders employed by the Defendants would re-join even when they moved to a different bank. They even one that it was common for traders to “fix[] spreads across chat rooms, by copying and pasting their text of one chat into another room.” The brief also stresses the degree to which participation in these chat rooms was considered to be an integral part of the traders’ jobs, quoting a former Credit Suisse trader who testified that his employer had “encouraged . . . us to use interbank chat rooms. During those chats we were asked to talk about what spreads were out there in the market at the time.”

Plaintiffs even point to an early chat—one which included a Credit Suisse trader—in which the participants expressly stated that they should “all agree on the same spreads” and agreed to “sign a pact on spreads.” While this specific “pact” included only a small handful of traders, Plaintiffs argue that “the traders’ social connections, the interconnected and overlapping membership across chat rooms, and [the traders’] supervisors’ insistence that traders participate in multi-bank chat rooms,” lead to a common practice of conspiracy and coordination between Credit Suisse and the other Bank Defendants. Similarly, Plaintiffs highlighted the testimony of Credit Suisse’s own former New York desk head, who had testified that traders “should not coordinate on spreads,” but also admitted that his own traders were participants in chat rooms sharing exactly that information. Plaintiffs quote several other Credit Suisse traders who admitted to using spreads shared in these chatrooms in their own pricing, and further observe that “[t]hree former Credit Suisse traders asserted their Fifth Amendment rights when asked whether Credit Suisse conspired on spreads with its competitors”—and that two dozen traders from other Banks asserted their Fifth Amendment rights in response to similar questions.

In opposition to Credit Suisse’s argument concerning the difficulty of coordinating spreads in a fast-moving market, Plaintiffs argue that spreads are “durable” in “normal market conditions” – so durable that traders created “spread grids” that showed spreads for various currencies over different trade sizes. They also point out that spreads correlated both vertically and horizontally in predictable fashion, meaning that information on one spread would allow a trader to calculate spreads for other amounts. Relatedly, where Credit Suisse highlighted the difficulty of simultaneously coordinating more than 52 currency pairs, Plaintiffs pointed out that 75% of trades are between currencies of G-10 countries, with just three currency pairs making up the majority of trades in the class period.

Rebutting Credit Suisse’s argument that the conduct only demonstrates a series of mini-conspiracies, Plaintiffs discuss the factors required to support the existence of a global conspiracy: “(1) an overlap of participants; (2) a common goal; (3) common methods; (4) knowledge of the conspiracy; and (5) interdependence among conspirators.” Each of these factors, Plaintiffs argue, have been met with sufficient proof: overlapping participants are present because each Bank was a forex market maker trading in the same currencies to many of the same customers; widening spreads was a common goal for all Banks; all Banks and traders used the same methods, namely, a “gentleman’s agreement” across the market, “founded on a common understanding that traders would provide [and receive] spreads”; general knowledge of the conspiracy, as opposed to knowledge of the “detailed scope” of the scheme is sufficient; and finally, with respect to interdependence, customers sourced quotes from multiple Banks, and the conspirators understood that they were not to use the shared spreads to undercut each other on price – as would have otherwise been expected in a competitive market.

The competing motions for summary judgment were fully briefed by June 2021, but a decision remains outstanding. With large settlements with 15 of 16 Defendants and multiple government investigations and settlements concerning the same conduct, it would be understandable if Plaintiffs are feeling fairly confident about their chances on summary judgment. That said, Credit Suisse has presented colorable arguments regarding the scope of the alleged conspiracy and the feasibility of coordination (and knowledge) on such a large scale. Time will tell what the Southern District thinks of the respective arguments, and we will be here to update you when that decision falls.

This post was written by Alexandra M.C. Douglas.